[Occupational therapy]–Boost Your Balance–Avoid Falls Exercises in 30s and 40s Can Keep You Steadier as You Age

If you find yourself needing to sit down to take off your shoes, it might be time to start paying attention to your sense of balance.

People don’t usually think about balance until they fall, but little signs such as relying on handrails to go up and down stairs can be early warnings that stability is starting to go, says Jason Jackson, a physical therapist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. These changes won’t show up on the formal assessments that doctors use for people with balance disorders, such as the Berg and Tinetti scales. For most people, good ways to gauge include the need to lean on armrests when getting out of a chair or feeling wobbly while standing with feet very close together.

An important age range for improving balance is the 30s and 40s. While most people don’t develop serious balance problems until well into their 50s, experts recommend that otherwise healthy people keep active and do simple exercises to challenge the body and keep steady into old age.

In the U.S., falls are the leading cause of injury for people over 65, according to a 2005 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Every 17 seconds, someone in this age group is treated in an emergency room for a fall. Every 30 minutes, one will die from injuries caused by falling.

Balance is controlled by the brain’s cerebellum, a region of the brain that is responsible for movement and coordination. According to McGill University physiology professor Kathleen Cullen, the cerebellum coordinates information from three systems: the visual, the vestibular (or inner ear) and the proprioceptive (or sense of body position). In addition, it works with the spinal cord to adjust for unexpected information—for instance, a slippery surface—and maintain balance.

All these systems start to erode after 40. And people also become more sedentary as they age and begin to rely on the visual system more heavily. The problem: The visual system doesn’t work as quickly as the vestibular system, so people start getting shaky and risk falling. “People then don’t trust their own balance, so they become more sedentary,” says Dr. Cullen. “And by becoming less active, you actually lose the ability to use or take advantage of [sensory information], and your balance gets worse.”

Exercises can isolate these different systems and make the body work harder to keep them in top shape. Experts suggest doing exercises in a couple of 5- to 10-minute bouts each day.

For people in cities with public transportation, avoid clutching tightly on to the poles in subway cars. A lighter grip will challenge your body to maintain stability on its own. Another option: Walk on many differences surfaces, says Mr. Jackson of Mount Sinai. When at a park, for example, alternate between walking on the pavement and the grass because the unstable surface will make the muscles work more.

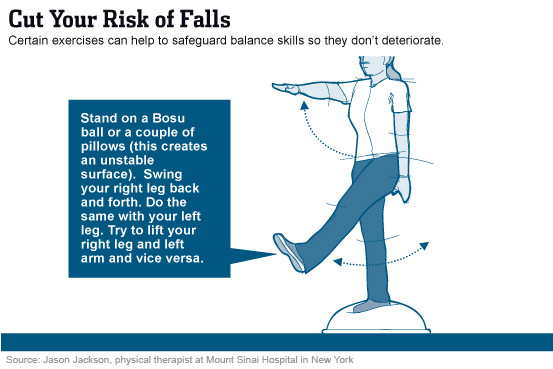

Other exercises:

At home, create an unstable surface by using either a Bosu ball or a couple of thick pillows. Stand on top of the ball or pillows and balance on one leg while swinging the other leg back and forth. Then switch legs and repeat. (If standing on a Bosu ball or pillows feels too challenging, try sitting on the ball with your legs straight in front of you and shift your weight from side to side.)

Stand and lift your right arm straight out in front of you while swinging your left leg back and forth, and vice versa, to work on coordination, says Mr. Jackson. Then try it with your eyes closed to help decrease your reliance on vision for balance.

Strengthening the hips—an important component of preserving balance—can be done next to the kitchen counter, says Jennifer Brach, an associate professor of physical therapy at the University of Pittsburgh. Hold on to the counter while standing on one leg and lift the other leg to the front, then the side, then back and then up with your knee bent like you’re marching. This works four separate groups of muscles in the hips: the hip abductors, hip adductors, hip extensions and hip flexors. (These muscles can also be strengthened by using the hip abductor and adductor weight machines at the gym.)

For office workers, simply getting up from a chair 10 times in a row can be useful, says Mr. Jackson. Alternate between getting up with your feet in wide stance, which provides more support, and getting up with a narrow stance with your feet touching.

“It’s much more difficult to maintain balance with a narrow base of support, so those little variations test your coordination,” he says.

Good balance also requires “exercise for the nervous system,” says Dr. Brach. “To practice their balance, people should be working with timing and coordination,” she says.

An exercise she has patients do in her clinic is the “stepping pattern.” Stand with feet shoulder-width apart. Put the right foot in front of the left, and shift weight onto the front foot so that the left heel is off the ground. Do this 10 times. Then repeat with the left foot in front of the right.

For a more difficult variation, alternate sides—go right-left-right-left—to get your body accustomed to switching weight more quickly, she says. You can also do make the move more challenging by stepping backward.

The stepping pattern is similar to moves found in ballroom dancing and “forces you to think and coordinate and time your body,” says Dr. Brach. Exercises that encourage learning new moves and adjusting to the environment—such as tennis or gymnastics, as opposed to long-distance running—may be better for maintaining balance. But, says Dr. Brach, “we don’t have the research to say for sure that one is better than another.”

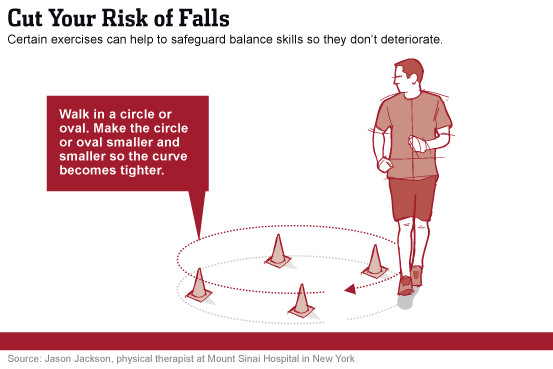

Walking in a circle or oval around the living room or backyard can be good practice because it is more challenging to walk on a curve.

There is also a mental component to regaining balance, says Arlene Schmid, an associate professor of occupational therapy at Colorado State University. This mental aspect is a bigger factor for people with impaired balance due to advanced age or illness.

In a study published by the medical journal Stroke in 2012, Dr. Schmid’s team taught yoga to post-stroke patients for eight weeks. Of the 34 patients, 19 initially had balance impairment as measured on the Berg balance scale. After training, 11 had impaired balance.

Dr. Schmid said she believes the patients were successful in large part because they felt confident they could do the movements.

“We really were trying to focus on making everyone feel successful from day one to build their confidence, so for the first few weeks we only had sitting postures,” she says.

Yoga can boost balance ability because it increases flexibility and its many poses integrate movements that strengthen a lot of different muscles, including those in the hip, says Dr. Schmid. But the emotional component is key.

“People are afraid of falling and they don’t want to move anymore—and the biggest preventative piece is just not being afraid to get moving,” she says.

Balance-Boosting Exercises

- Walk in a circle or oval. Make the circle or oval smaller and smaller so the curve becomes tighter.

- Stand on one leg (hold on to a counter if you need to) and do leg lifts to the front, side, back, and up like you’re marching. This exercises four groups of muscles in your hips, which are important to preserving balance.

- Get up from your chair 10 times in a row without leaning on arm rests. Alternate between your feet in wide stance and close together. Make it more difficult by closing your eyes.

- Put five cones (or other objects) in a straight line and weave between them.

- Stand with feet shoulder-width apart. Put your right foot in front of your left, and shift your weight onto your right foot so that the left heel is off the ground. Do this 10 times. Repeat with left foot in front of the right foot. Variations: Do the exercise alternating feet or stepping backward or with your eyes closed.

Sources: Jason Jackson, Mount Sinai Hospital in New York; Jennifer Brach, University of Pittsburgh

![[Occupational therapy]--DSM-5 ASD&SCD Diagnostic Criteria [Occupational therapy]--DSM-5 ASD&SCD Diagnostic Criteria](http://i0.wp.com/farm6.staticflickr.com/5441/9152067179_b53008cd5f_b.jpg?resize=300%2C200)

![[新北 板橋]--鴛鴦壽喜燒--Suki-Ya板橋店 [新北 板橋]--鴛鴦壽喜燒--Suki-Ya板橋店](http://i0.wp.com/leosheng.tw/wp-content/uploads/pixnet/0b1ffd97ec689e30d41a6f75c5cee92b.jpg?resize=300%2C200)

臉書留言

一般留言